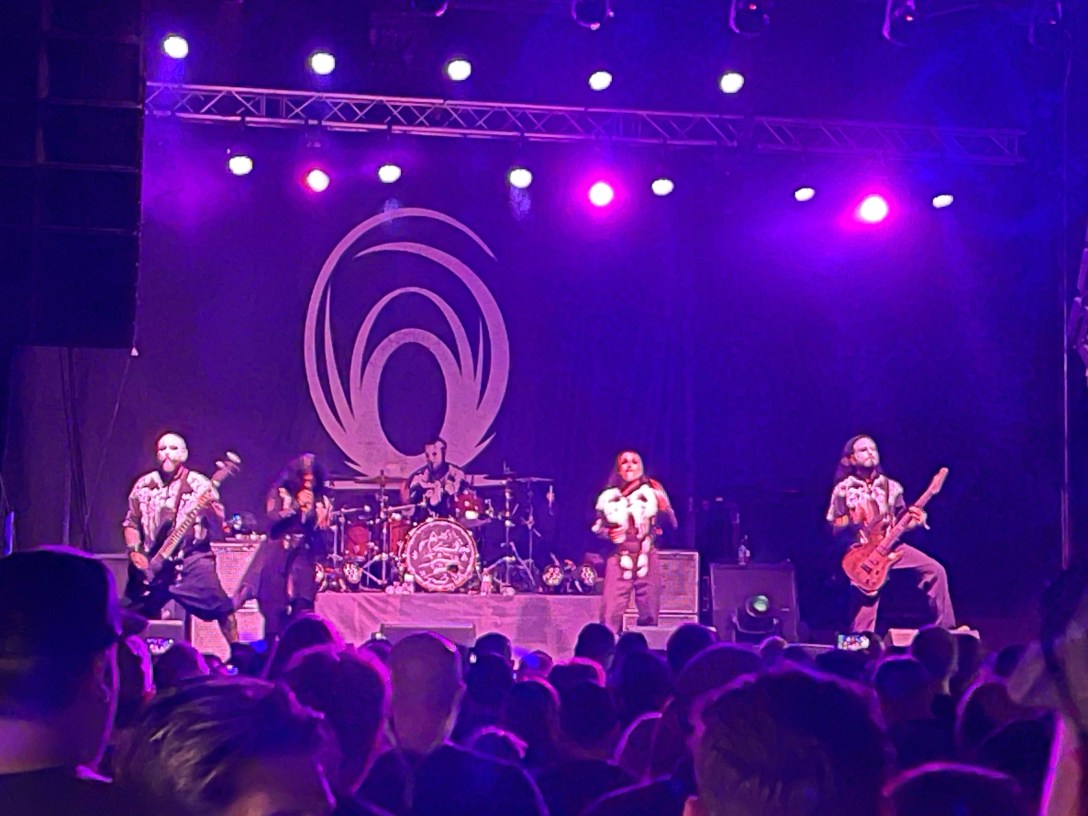

Look, another band for you to identify from another concert I attended. This one is probably much easier to identify because of their very unique costuming. I’ll post the name at the end.

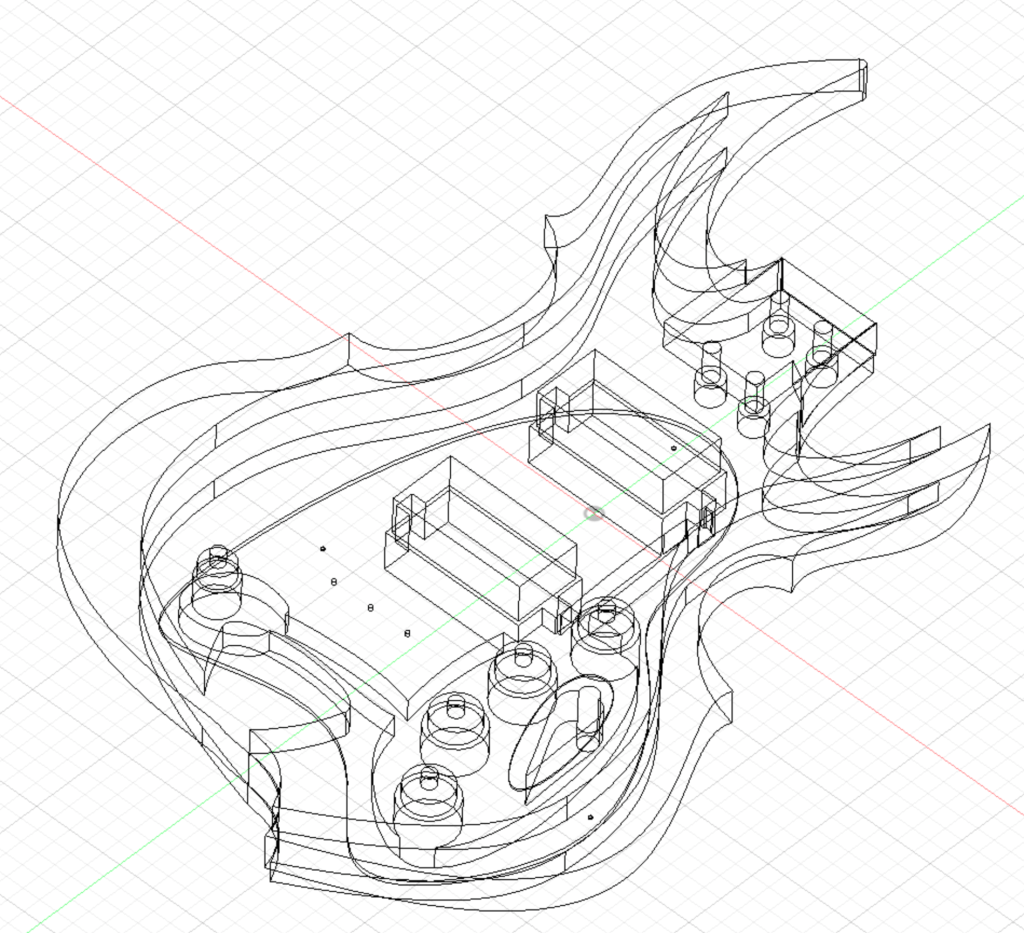

You can follow the journey so far by following these links: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3. I’d also like to point out that I’ve managed to stick to this project for almost 8 months now. I must really like it.

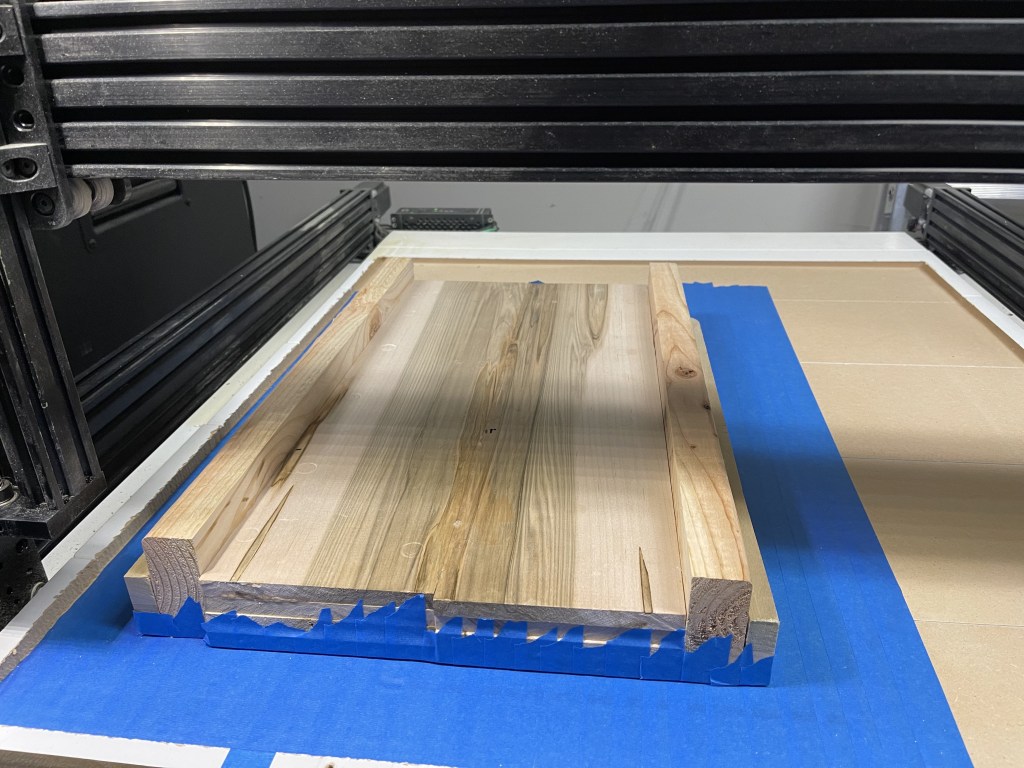

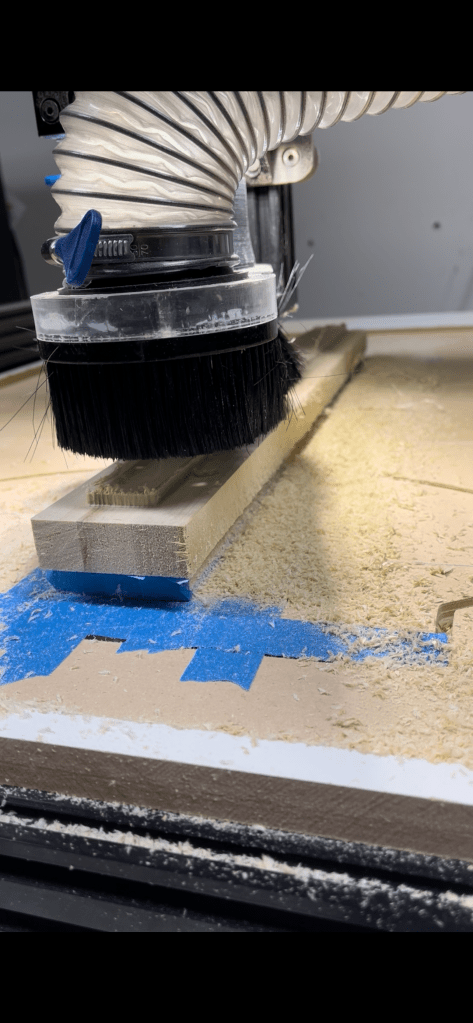

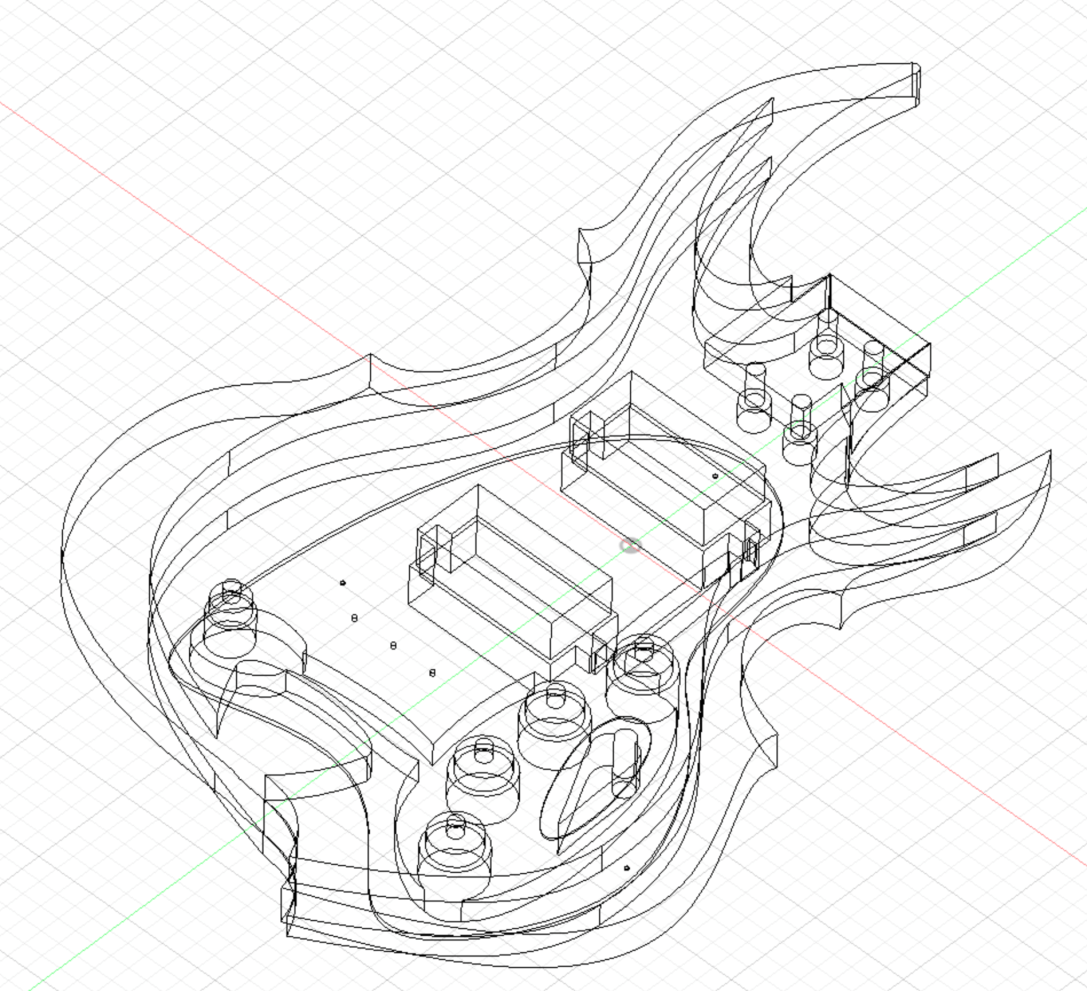

As mentioned in my previous post, I didn’t want to run super agressive cuts because my real stock had cost me so much. Not to mention it has some of the most beautiful figuring I’ve ever seen in wood and I’d never be able to find it’s equal again. This means that it took days for the cnc router to cut it to shape. Looking back now, I totally could have sped it up, but I don’t hate that I took my time.

As a side note, padauk has a super pleasant smell. While doing a surfacing pass, I had the router rotating at a bit too high of a speed and scorched the wood in certain places. It smelt like incense. Slowing down the spindle still produced a pleasant smell. In fact most of the woods I worked with on this project smelled very nice.

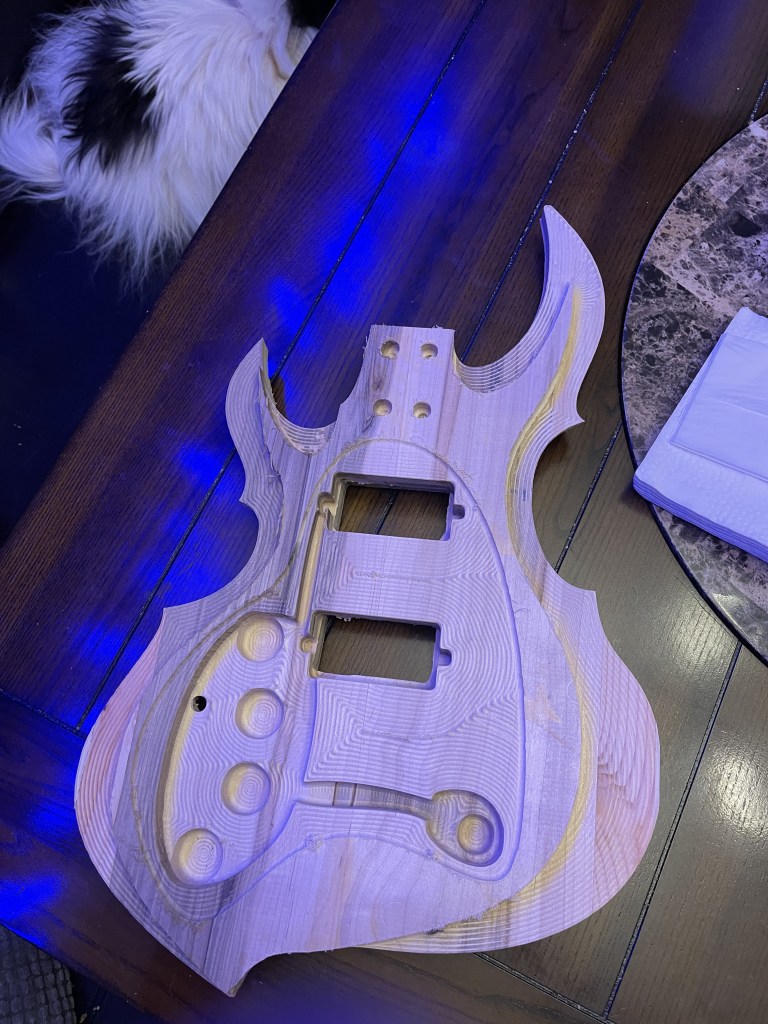

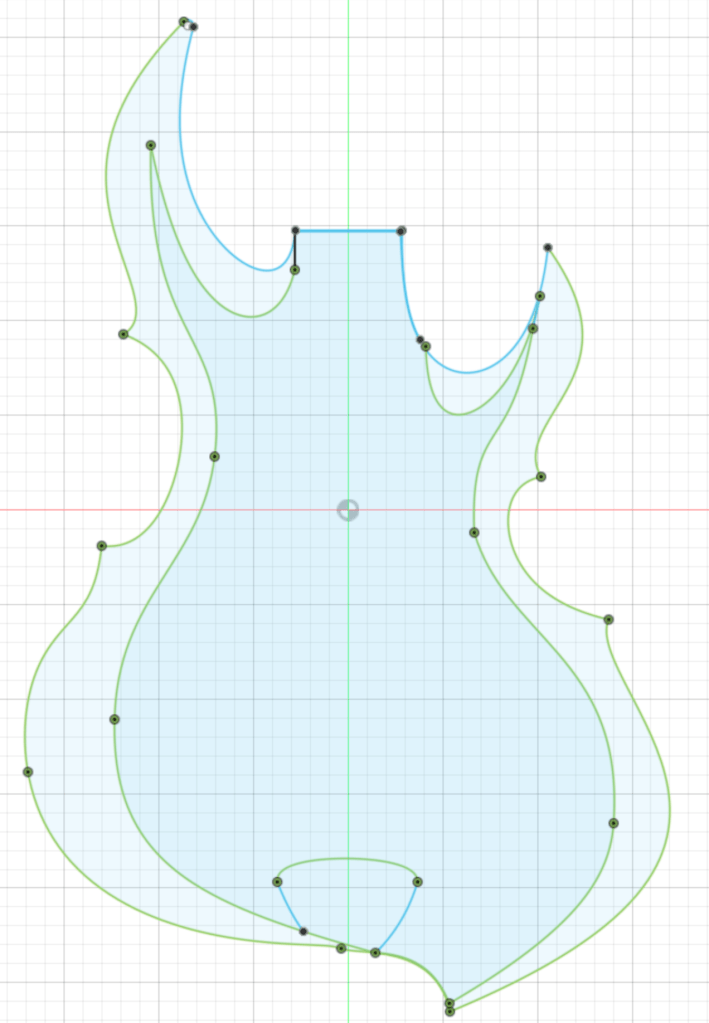

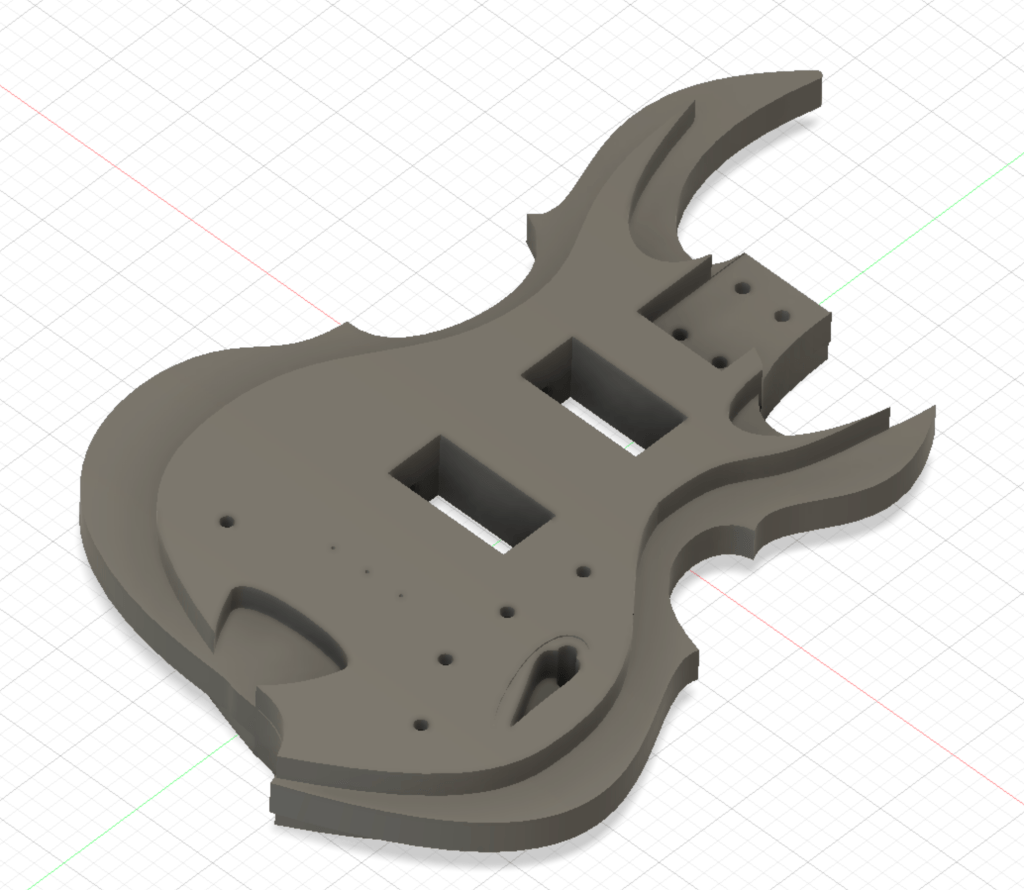

Despite my best attempts I was unable to align both the top and the bottom cuts of the body, so using my new rasp was necissary.

This only took a few minutes, but did change the shape slighly (about 3-4 mm overall) and offset the back and front inner cuts slightly and I had to fix those too. Most specifically, the pickup holes were off a bit and I could not fit the pickups through the holes and I had to spend the rest of the night evening those out.

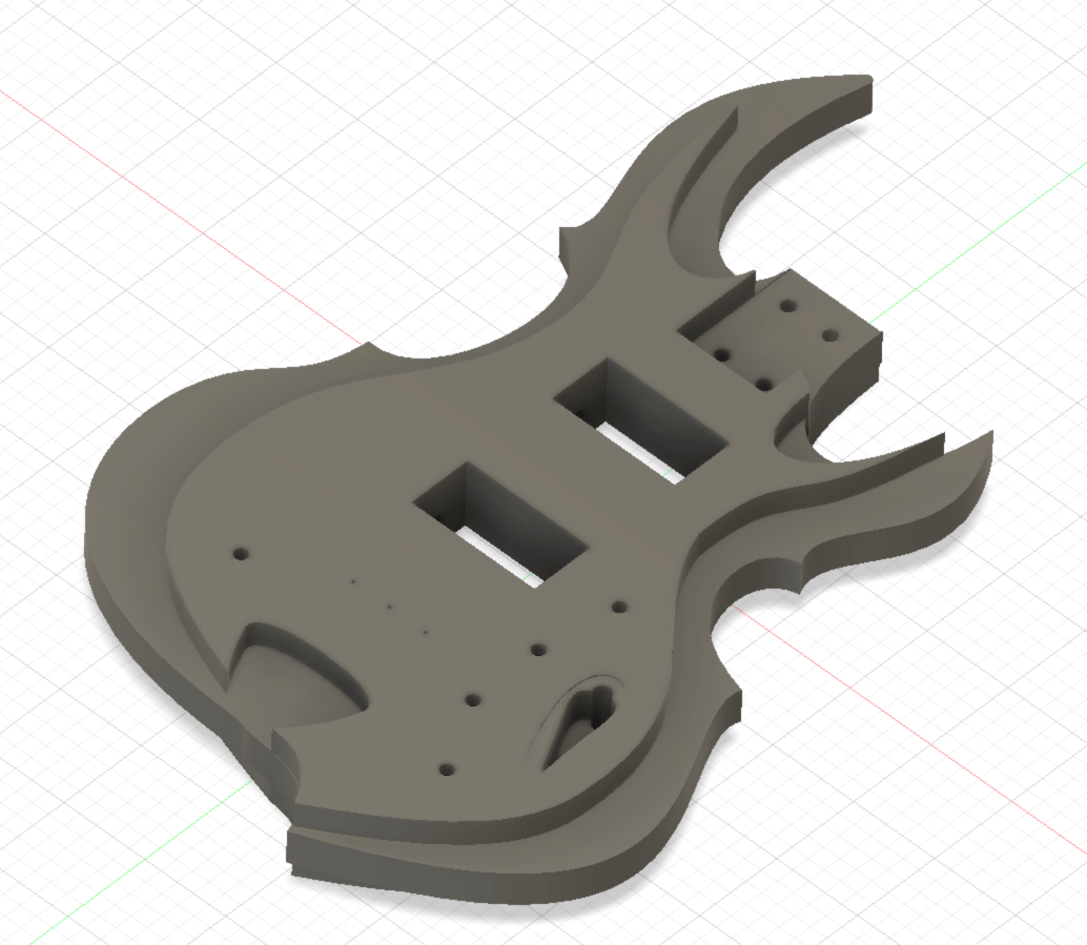

Another quick note about pickups. In most guitars, the pickups are connected to the pickguard and pulled toward it by the mounting screws, not screwed into the body of the guitar and held away from the wood. Unfortunately for me, I believed the second to be the case, and had based my design on being able to screw the pickups to the wood from behind. Once I realized my mistake I tried to quickly pivot and fix the problem and add plates around the pickups, thinking this was the only way to correct it. If I’d have thought a little bit longer I could have realized that I still might have been able to mount the pickups through the wood by thinning out the body in that area and mounted the pickup through the body just like a pickguard. Hindsight, right? Anyway, I designed and laser-cut these plates in black acrylic.

Once the body was done, I began the neck run. The neck wood I had chosen was zebrawood, and again, I had the problem with the top and bottom being offset slightly. Once I rasped the edges flat, the groov for the truss rod was too far left and the rounding of the bottom was too far right.

I had just received my wood carving tools and with them, a draw knife. I’ve never used any of these before, but the draw knife seemed like the perfect tool to even everything out. Short story shorter, it’s not. See, wood will tear along it’s grain if you catch it wrong. And I caught it wrong. In just 3 draws I managed to tear the neck nearly in half. So I had to order more wood. This time I wanted to avoid zebrawood and went with purpleheart.

I ordered two pieces of wood for the neck and once they got here, I got to cutting the first one on the cnc machine. And while that was going, I started in with my carving tools on the body to round out the edges and try to finish up the shaping.

The towel is to try to keep the vice from marking up the wood.

I bet you’re expecting me to give a list of problems I had with the carving tools. Well, the answer is “nothing.” This time I paid attention to the wood grain and how the wood behaved under the gouge and went slowly with short cuts. Things turned out good. I made sure to leave myself enough to finish the shaping with some 80grit sandpaper.

Buuut, while I was carving away, I found out why you needed to have enough masking tape on the table. While cutting the channel for the truss rod, the first neck wood came loose and rode up into the router’s spindle, driving a 5mm groove right through the neck, and then tearing out the side. I tried to figure out how to save it, but the neck was gone. Time to toss this one in the scrap pile to figure out what I can make of it later and start on that last neck.

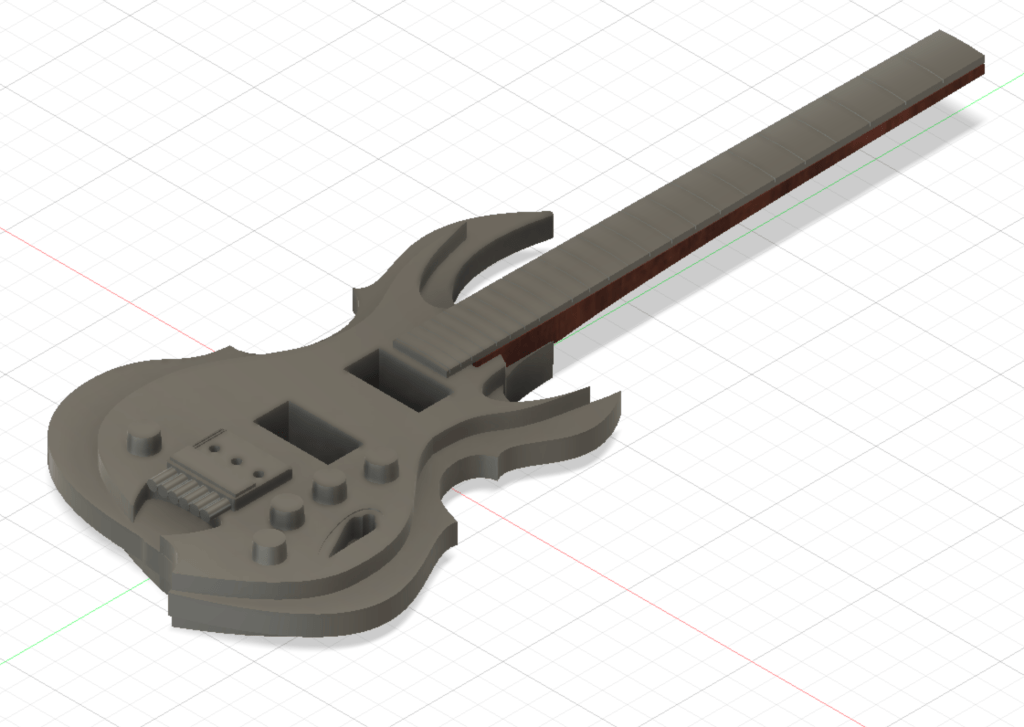

Finally, this last one came out fine. Slightly offset, but I made sure to leave myself some room for sandpaper corrections. Fretboard, some black walnut, came out fine on the first try too!

This picture is a little bit early in relation to my story, but it’s the only one I took with all 3 separate parts.

Anyway, I’ll pick up from here in my next post.

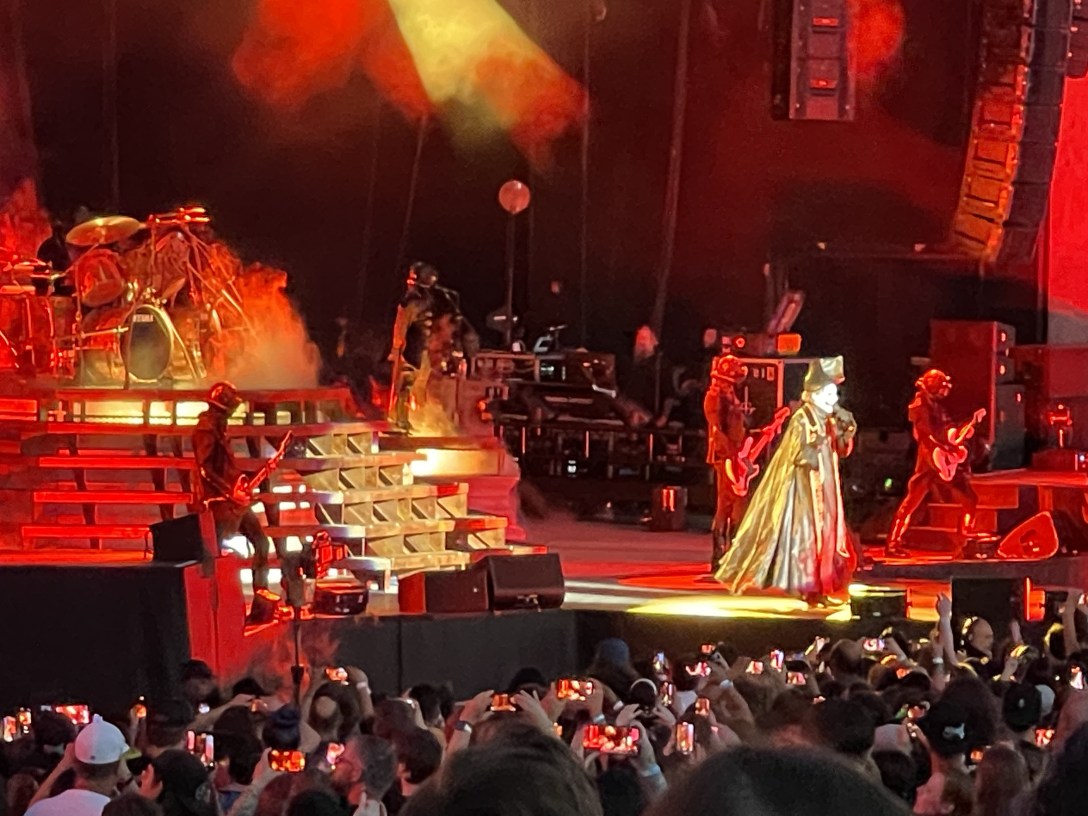

And as promised, the band in the featured image is Ghost. The show was very fun; lots of visuals, lots of costumes, lots of loud, and lots of interaction. This was an outdoor show, and the weather leading up to it had been insanely hot (100 degrees plus). Luckily the night before it had rained and during the show it was threatening to rain, so we didn’t die, and the band didn’t die. The music might not be for everyone (with a lot of devilish overtones), and the theatrics might not be for everyone, but I thought it was great. I recommend going to a Ghost show if you get a chance.